[Tokyo Rain by John Paul Thornton]

"What is Wabi-Sabi?" I asked.

It was a rain-drenched evening in Tokyo. A typhoon had hit earlier that day, spawning seas of bustling umbrellas beneath the towering neon skyscrapers of the Blade-Runner like Shinjuku district. In the midst of the flury I had been driven by a pair of Japanese artists to the Tokyo Museum of Art. We could be dry, and become lost in the comforting quiet that museums extend to the weary.

“What does Wabi-Sabi mean?”

The question was innocent enough, but my Japanese hosts just responded with big smiles that grew into nervous laughs. I stood there in the middle of the Museum, waiting for them to answer me. Instead, they turned away as if the matter were closed and walked ahead to silently ponder a ceramic bowl.

Say “Wah-bee Saw-bee”

I had never heard of the word Wabi-Sabi until my hosts had begun whispering it to each other while they strolled through the art exhibits. What was Wabi-Sabi? I was intrigued by the sound of the word and the reverential expression that fell upon the faces of my new friends when it’s little song passed their lips. Boldly, I approached them again to translate this new word in English for me.

“Really guys, what does Wabi-Sabi mean?”

My third request was only met with more nervous laughter and awkward silence. We took a break for Sakai at the Museum café. After a few drinks and further discussion about Japanese art, I boldly asked them again about the meaning of the word I had heard them use. Finally one of my hosts, a famous Japanese artist, turned to me and with his brow furrowed in thought he spoke:

“There is no… precise translation for Wabi-Sabi” Then he said: “Imagine a landscape. It is night. The full moon hangs in the sky but a cloud passes before it, obscuring it. A jagged tree is silhouetted against the luminous sky. A breeze causes gentle movement in the branches. Far away a dog barks.” He fell silent and eyed my reaction, which was to sit dumbfounded before him.

He began again. “A wall of rock rises beside a well-worn trail. The rock is covered with moss and is marked with fissures and cracks from centuries of winters. A single delicate flower grows out from the rough surface.”

I realized that he was answering me in koans, a Zen Buddhist tradition of presenting a student with an unanswerable riddle.

Still, I did not fully comprehend. My new friend took pity on me. He shrugged and then cautiously gave me this answer: “Wabi-Sabi means…beautiful imperfection.”

Beautiful imperfection? I dared not pester them with more pleas for meaning, but I wanted to better understand. Equipped with this concept, we re-entered the museum and came to a room filled with four hundred year old cooking ware and painted screens. We passed by a row of perfectly formed tea cups with exquisitely decorated rims so that we could admire a single slightly misshapen cracked bowl, whose colors were varied and muddied. Instead of a smooth finish, it was uneven and subtly blemished. I continued to stare at this vessel for a while, unmoving and silent.

My brain was still reeling from the glamour of Tokyo. The neon colors and frantic activity of the city had to be pushed away. I focused on the stillness of the room as I relaxed my breathing. Finally my impatient mind and chatty mouth quieted. I became aware of the bowl and all of it’s features. It was delicate yet rough. Crooked yet functional. Ugly yet compelling. Imperfect and beautiful. Without words I was then escorted to a display case containing a faded wooden folding screen onto which was painted a flurry of brushstrokes representing a cherry tree in an open field. A hazy mountain pierced low-laying clouds in the background. As I paused, the active disunity of the brushstrokes merged to form a complete motif. I became aware of each stroke, and each decision made by the artist. I noticed the emptiness between each brushstroke and the silent mood that the image evoked in me. The worn surface of the wood hinted at...what? Nostalgia, reverence, dignity.

I felt calm and giddy. My heart raced as I experienced a kind of sensation we artists feel when a great ignorance is removed from our perception and we encounter truth. The rest of the day, everything was transformed to my eyes. The remainder of my stay in Japan was a finely tuned awareness which has continued on into my life ever since. Visual aspects of the world have become almost magically enhanced. This has led to something else: I became aware of my own painting in ways I never had before: I became aware of what I now call poetry.

Wabi-Sabi is really two words, each with a deep and nearly untranslatable mmeaning.

Wabi stems from the Japanese root wa, meaning “peaceful,” “harmonious” and “at ease.” In it’s original meaning, wabi had a slightly belittling connotation of loneliness or sadness- withered or bleak. Yet it has now come to describe a healthy sense of humbleness and balance.

Sabi translates as “the effects of time”. The effects suggested are natural and part of a greater process. Think of how Rust overcomes an abandoned car in a field, turning it picturesque. Visualize the way surfaces fade and crack… how wrinkles overtake the skin of a woman as she gracefully ages or how intricate weeds entangle a neglected garden.

If Wabi means humble, and Sabi means weathered, then we have the exact opposite of the Western ideal of “perfection” nurtured by the Greeks and later by Europeans during the Renaissance.

America does not have a true phrase that is the equivalent of Wabi-Sabi. “Beautiful imperfection?” We have no such thing. We have adjectives like “antique,” “rustic,” and “weathered,” but these describe more of the imperfection of a thing rather than it’s beauty. We have phrases like “happy accident” or “controlled chaos,” but these fall short as well, sounding more like apologies rather than philosophies.

What I did rejoice in was the realization that this state, this feeling or whatever it was, was definable. Wabi-Sabi was something I had always loved and craved. It was the explanation for why the crumbled surfaces of paintings by Rembrandt radiate with such profound richness.

[Detail of Bathsheba by Rembrandt]

[Blind Philosopher by Rembrandt]

The European old masters allowed the paint variations to exist, unblended in their art. They applied paint with their fingers, or with their palette knives. They sought for a “feeling” rather than the visual replication of things.

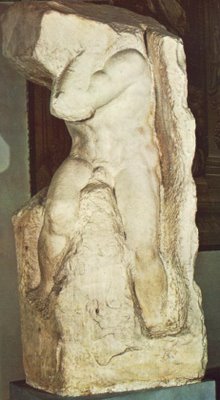

Wabi-Sabi was the answer to the secret of Michelangelo’s unfinished marble figures called “the slaves” who appear to be still trapped in marble. They are half visible and half obscured, just like the moon had been described to me in my Japanese friend’s koan.

[The Slave by Michelangelo]

Wabi-Sabi was the hidden power behind the paintings and sculptures of the impressionists, whose glorious images of atmosphere and light seem to fall apart as the viewer steps closer to examine the surface of the canvas.

[Impressionist Sunrise by Claude Monet]

While much of the story of contemporary European and American painting has been a mad race to define “imperfection” as being pure ugliness, a similar effort has been made to define “beauty” as slick and neo-classical. What is missing is a striving for balance, a harmony of parts. Whether Western or Eastern, art is at it’s most dynamic and mature when it is drenched with “Wabi-Sabi”.

Of course,taking an ancient Japanese aesthetic and attempting to fit it into Western cultural experience may be looked upon as the height of ugliness. Then again, we are all linked to this sensation. While we all share an unspeakable longing for resolution, we withdrawl inward to remember and reflect. We all know the feeling of slipping our feet into worn, comfortable shoes.

Wabi-Sabi allows for personal expression, and individuality. There is a subtle quality that this implies- not the bombastic rush of adventure, but a quietness, or a transformation caught between phases. It is a lack of predictable precision. It is what we call A sense of mood.

Yet beyond art, we might go further in it’s broad implications. “Wabi-Sabi” could be a freeing way of approaching life. Embracing “Beautiful imperfection” would allow us to find poetry in the aspects of daily living which we now ignore or deplore.

Discover it in your world sometime unexpected, quietly.