"I would like to exert influence in these times when human beings are so perplexed and in need of help-"

These words were written by a mother whose son was taken from her during a ravaging war. This fact alone did not differ her mourning and grief from that of hundreds of thousands of other mothers across the cycles of human history. She was also an educated, articulate teacher holding prestigious honors. This could have been said of thousands of people, but rarely about a woman living in a male dominated Germany in 1922. All of These honors were to be suddenly stripped from her, (or deliberately shedded by her), as the fascist machine called Nazism gutted Berlin along with all Deutschland of it's cultural decency.

This particular woman was an

artist, and this made all the difference in her journey. It ensured that she would not be barren after her losses. It ensured that her existence would not be erased by the cruel boots of evil. This one aspect above all ensured that there now exists a record of her pain, her strength and her amazing life...

The woman's name was

Kathe Kollwitz. She was an artist who would not crumble. She would not sell her very soul to the devil or embrace a false ideal in exchange for promises of safety. For this, Kathe (pronounced KAY-teh) is a champion hero and a model that all humans should hold in their heart. She is the embodiment of art and courage. Kathe's art is like a time-released message to us, sent from a past century to our own.

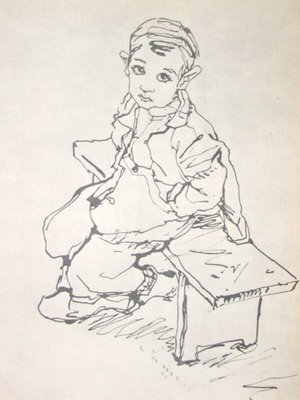

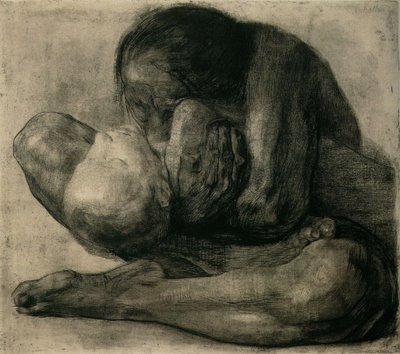

When I first saw a work of art by Kollwitz, it was a defining moment for me. I was eighteen, in art school, and had bought a book on "expressive drawing". My first exposure to Kollwitz was her lithograph,

A Woman with dead child. It resonates with the greatest strength and the most authentic sensitivity I can imagine. The design appears as if a rock has been tossed into a pond, and the ripples radiate outward from the center. While kathe was a master of human anatomy, she does not waste our time, or her own, by rendering every body part simply for show. She selects the most vital elements. It is anatomy in action and anatomy with meaning. She gives us unflinching clarity and soft mystery, while she conjures horror and intimacy. Line merges with stain and death marries life. She created the image by looking at herself, posing in front of a mirror with her own eight year old son, Peter. It was to become a prophetic image, as years later, her son would be killed in the first days of World War One.

Her images trigger emotion in me, and more importantly, I believe the emotion that came from her. I believe her anger, her compassion, her pain, and her ability to understand that her experience did not belong to her alone, but was (and would sadly be)shared by so many mothers across time and space.

Kathe Schmidt was born on July 8th, 1867 in a city named Konigsberg in Prussia. She was raised by a strong and caring family. She studied painting at an early age, and was soon enamored with the expressive techniques of etching and printing. Ink drawing was her real passion. Linework and graphic black and white presentation gave voice to her style of realism. Having visited Paris and Venice and seen much of the current style of colorful Impressionism, Kathe's choice to remain so dark was a reflection of artist max Klinger's writings: "Some themes should be drawn rather than painted. Some themes would be ineffective and even inartistic if rendered by means of painting." He taught that the darker aspects of life were reflected better in graphics. She embraced this belief, and immersed herself in drawing.

In 1891 she married a young Doctor named Karl Kollwitz who happily set up a studio space for his bride and then set up his own office across the hall. It was this situation that gave Kathe intimate views of illness, poverty, malnourishment and especially the plight of poor children in her community. Politics and history began to play heavily on her mind, and her primary successes as an artist came from a series called

The weavers. It was one of the first bodies of art created in which a struggle for a better life by working class people was depicted sympathetically. When displayed at the Great Berlin Art Exhibit in 1898, a distinguished jury awarded the Weaver's cycle with a gold medal. Kaiser Wilhelm II feared

The Weavers'social content, and referred to Kathe's work as "gutter art." He personally blocked the award from being given. This Veto was only the beginning of the censorship and discussion that would ultimately surround her creations.

Success and opportunity in her career was matched by happiness in her life as a wife and mother of two sons until the onset of The Great War when her youngest son Peter was killed in 1914. He had become filled by pro-military rhetoric and volunteered to become a soldier. Kathe

the mother never recovered but Kathe

the artist was empowered by this personal tragedy. She became the voice of a cause that could not have been more passionate. Her previous cycles of strikes and etchings of peasant rebellions were ultimately mere rehearsals for her own stand against war, or more specifically; those who destroy youth in order to employ them as soldiers. One of her favorite axioms was "Seed for the planting must not be ground up." The seed she spoke of represented the promising generations of children who are sytematically erased by the ever seductive war machine.

Her work became unflinchingly social as she created art to rally viewers against hunger, political corruption, abuse, and apathy. With her bold graphic style, she pleaded for compassion and action. "Peace" after the end of the war meant only humiliation and despair for the powerless citizens of the defeated Germany, and the treaty of Versailles left the Nation unable to fully reform. It took the evil Adolph Hitler to fan the embers of bitterness and despair into high reaching flames of ravenous Nationalism.

Hitler was a frustrated artist himself, who had received poor response from his architectural drawings as a student in Vienna. Along with his frightening plans to create a new Germanic empire, he believed that German art had been corrupted by contemporary ideas and anti-military social messages. When he obtained full power, newly blacklisted artists across the country were pressured to stop painting and Forbidden to exhibit. Kollwitz herself was forced to resign her position as an art instructor, and her works were removed from public museums. She was "courted" by the Third reich, who wished to have her return to the fold and retain her place of honor as one of Germany's greatest artists, if only she would renounce her previous work and produced art along party lines. While thousands of other citizens in all walks of life submitted to this kind of fascism and desperately sold out, Kollwitz would not.

Her work became illegal. Her shows were shut down. On one occasion she was threatened with being sent to a concentration camp for not cooperating with the Nazi police. When the newly constructed "House of German Art" exhibited eight hundred examples of art that Hitler approved of, she was not invited. Nor was she included in Hitler's infamous

Degenerate Art Exhibition, where examples of art deemed unclean and unfit for viewing were mockingly put on display in a kind of "house of horrors" freak show. Worse perhaps than being ridiculed, Kathe was ignored by the State.

She remained in Berlin as many of her artist peers were purged from society. most fled or were imprisoned. She worked in private, and sent her drawings to New York, where she developed an enthusiastic following. With the outbreak of World War Two however, her ties to the U.S. were severed.

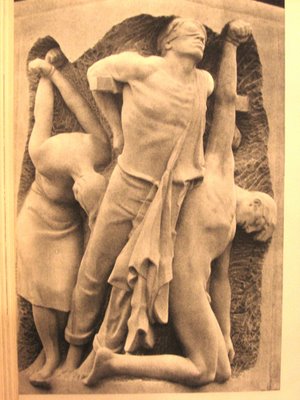

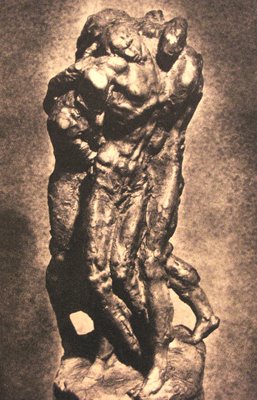

As Nazi propaganda boomed that Germany was winning the war, soon the truth was obvious. Allied planes launched unflinching retaliatory attacks against German civilian centers. Her own home was bombed during the intense air raids by allied planes, and her Grandson was among the dead as the country fell. She died on April 22nd 1945, just a few days before the total surrender of the Nazis, not knowing peace or the outcome of the War. Her final great artwork was the monument to all parents of dead soldiers.

The Mourning Parents depicts two kneeling figures gripped in physical and internal torment. Different from the typical Christian pieta, there is no body to mourn. Instead, there is only a void...An empty space. It is a self-portrait of the artist and her faithful husband created for a cemetery in Belgium. A replica now stands in the preserved ruins of the Saint Alban church, beside the Rhine river in Cologne.

Cologne is also the home of the intimate and comprehensive

Kathe Kollwitz Museum. Located above the bustling Neumarkt, visitors take an elevator to arrive at a world-class sanctuary of her art. The Cologne museum was specially built to retain the mood and scope of this amazing woman's commitment to the preservation of life. For all of the darkness and visions of death that emerge from her graphic work, it is her strength that is victorious. Unlike many glum symbolist, surrealist and expressive artists after her, Kollwitz created art which is firmly planted in the knowledge that humanity can live in a civilized realm of dignity and love. It is this love that keeps her images from becoming merely horrific. It is the dignity that helps her work transcend the mere political. To think of her work as being linked to a long-gone European crisis is a great mistake. Sadly, infact, her work appears to be timeless.

Our own time is ripe for the message of her universal artwork. The fervor of a handfull of men (always men...) is once again fanning flames into wars that defy reason. Every day, one can watch the news and observe children torn apart by car-bombs in the name of retribution, or air strikes in the name of liberation.

It is the numbingly cliched constant story of our advanced epoch. I am keenly aware of the cycles of history, and wonder how many Americans could hold to their heartfelt beliefs as firmly as old Kathe did if ever faced with the choice. Perhaps many of us. Perhaps a few. How would we respond to Fascism?

In any case, how governments treat their artists seems to be the canary in the coalmine of civilization. When the arts are free, people are free. When arts funding is up, culture flows. When art expression is valued, fear disappears. When these fruitful rules are not in play, the opposite will be true.

Kathe devoted her life to creating a kind of warning mechanism. Her images seem to be taken from out of today's world news instead of belonging to faded chapters from yesterday. We should allow ourselves to question the direction that a half-a-dozen or so world rulers are steering the Earth. Without a doubt, If we follow the old course, we will come to view her art as simply proof that "others had tread this way before".

Others before us lost their babies.

Others before us stood in long bread lines.

Previous neighborhoods have been obliterated.

Similar anthems were once shouted.

Kathe hoped for a change in this cycle. As she died in the last days of the second world war, she could have only hoped that the people and cultures of the Earth would somehow survive. She probably wished that her art would speak to others in a future century, to remind them that we all share the same salt in our tears, the same habits of heart and the same ability to have courage when we are led astray from the path of wisdom and peace.

Experience her work. Treat it as a gift. She created it for us.